|

Andrew Revkin at New York Times Doearth and through the tragedy of the recent Italian earthquake, sparked an important question on why people live in disaster zones and the challenges of engineering for hazard zones. He invited me to submit a comment. His original and thoughtful piece along with my comment is posted here and my comment is in the blog below.

New York Times: 6:3o p.m. | Deborah Brosnan, a scientist focused on disaster risk reduction (and an author of an important report on planning for extreme geohazards), sent this relevant reflection: A sense of place is core to all cultures. The older the culture the deeper the sense of place. The U.S. is a new country. It has a stronger sense of political identity than it does of physical structures and places. Our treatment of this complex issue is not as sophisticated as it needs to be. We send mixed messages. Humans have traditionally settled in harm’s way because natural hazards are associated with resources that we need, like water and food. Cultures persist when the losses do not destroy them completely. In conservation, we acknowledge and vigorously foster the sense of place as the critical bond between humans and their environment. We argue that it’s key to sustaining our planet. Yet when hazards become disasters we focus on the dangerous “place.” I grew up in the west of Ireland where the sense of place was enshrined and all-defining. Many of my ancestors had left during a disaster known as “the famine” and the ruins of their homes still dotted the landscape. For those who didn’t leave the bond between land and people grew stronger, and having land was a mark of a person’s worth. When I worked in Sri Lanka after the Southeast Asia tsunami, many of the displaced survivors were housed in U.N. tent communities. But during the day or even at night, they’d go home. I saw them sitting on makeshift chairs in places where there was barely a foundation left or nothing at all. Their “home” was their only anchor in a world that had been turned upside down, and where other anchors like family and friends were gone. But they were also afraid, fearful that if they didn’t protect their property then someone else would move in and squatters would take possession. I witnessed similar feelings and behaviors when working through the volcanic eruption in Montserrat. A nation’s cultural history, relationship to natural resources, and frequency of hazards all determine the sense of place and the meaning of leaving or changing. Rural Italy, like the west of Ireland, has a deep sense of home; however risky, it’s an established known. This is a complex subject that runs deep in our D.N.A. and evolutionary history. The way we handle it will determine how well we navigate climate change. Thanks for starting the conversation that we need to be having. Deborah Brosnan

0 Comments

If you are involved in producing, reducing, or managing carbon emissions, then listen-up because this will affect you.

Last week the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals might just have made one of the most critical climate change rulings to date. By affirming the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC), it will encourage other regulators to use carbon costs in setting policies, and may pave a way for a Carbon Tax – an idea much feared by some. But it also offers an opportunity for companies to quantify and communicate the energy value of their technologies, and the dollar value of their environmental and social practices. In a Chicago courtroom, the justices (all, incidentally, appointed by Republican Administrations) upheld the Department of Energy’s (DoE) metric on the Social Cost of Carbon, under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA) of 1975. EPCA was enacted in the wake of the Oil Embargo on petroleum exports to the US by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries in 1973-74. EPCA was enacted to help and protect the US through the use of energy conservation measures. In 2014, the DoE issued two rules, one set the energy efficiency standards for 49 classes of commercial refrigeration equipment and the second stipulated the test procedures to be used. Several industry groups filed suit challenging the substance of the rules and the decision-making processes used by DoE to make them. One of the challenges concerned the Social Cost of Carbon (SSC) metric which DoE used in its cost-benefit analysis for setting new standards, an analysis required since 1981 whenever the agency considers new regulation. The SCC represents the economic cost of damages associated with a one metric ton of Carbon in a given year. (The same figure represents the value of damages avoided for a reduction in Carbon). The metrics were generated by an interagency panel comprising experts in science and economics from 15 agencies and first formed in 2009. The current dollar value is US$37* per ton. What does this mean? If for example tightening certain emissions standards lowers carbon output by say 3 million tons per year, then multiply the number by $37 and you have the total damages avoided ($110million). SCC is designed as a comprehensive estimate of climate change damages and includes among other factors, changes in net agricultural productivity, human health, property damages from increased flood risk, and changes in energy costs (heating and air conditioning). It does not however include all kinds of important damages e.g. extreme disasters are excluded. For the proposed rules on commercial refrigerators, DoE calculated that the new conservation standards would cost manufacturers between $93.6 and $165 million per year. At the same time the projected total benefits to consumers was estimated at between $4.9 and $11.3 billion, including in green house gas reductions and consumer savings. DoE used the analysis as one criterion to justify the standards. The petitions challenged the figures and the methods but the court repeatedly sided with DoE. The petitioners argued that in its calculations the DoE arbitrarily considers the benefits accruing to the global environment and to all people around the world, but only considers the costs on a national level. DoE argued that climate change involves a global externality, meaning that carbon released in the US affects the entire world. National energy conservation, the agency argued, has global effects and these are an appropriate consideration for national policy. The court agreed with DoE. In its 68 page ruling, the court denied the petitions for review in their entirety. The implications of the ruling are enormous. First the court definitely ruled on the legality of carbon accounting, and the use of quantitative measures of carbon cost-benefits. We can anticipate more regulators to incorporate SCC when considering and justifying the need for new or revised environmental regulations The acceptance of a quantitative carbon accounting provides a dollar value that has potential implications for a Carbon Tax. This is a highly controversial topic. Several entities feel that there must be and will be a carbon tax while others are vehemently opposed. The ruling may be good news for certain businesses. Deriving a dollar figure for carbon will help businesses plan for the long term. Being able to credibly quantify costs and benefits of new technologies and corporate actions has long been an impediment to companies. Consumers and shareholders relate to numbers. Companies will now be able to disclose their environmental and social performance to shareholders and stakeholders and in better and standardized way. The case was a complex one involving science, economics and policy. There are many lessons in the ruling including for scientists as well as environmental attorneys who use science in their practice. Critical to the case was the conclusion that the agencies had relied on science that met the current professional or industry standard, was peer reviewed and evaluated in an open and transparent manner. The court also considered and accepted the use scientific uncertainty standards, something that can be challenging in courts and a rarity in complex situations especially regarding climate change. The social cost of carbon once an emerging instrument in putting a price on carbon has just become the center-piece. *(Several entities argue the figure is too low e.g. a recent Stanford Study calculate SCC at $220 per ton) This appeared as an Opinion Piece in the Sunday Washington Post here Thanks to the Post for publishing this opinion.

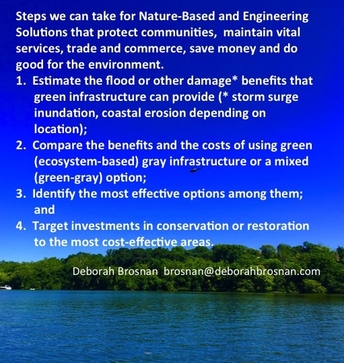

Last weekend we witnessed incredible devastation and tragic loss of human life in Ellicott City. The full scope of the disaster won’t be assessed for some time. For many residents, just feeling safe again will be challenging. Ellicott City sprung up in a bucolic countryside surrounded by rivers and streams and is naturally prone to flooding from the Patapsco River and Tiber Creek. Flash flooding from this storm, which dropped about six inches of rain in two hours, was an extreme event but one that may become more common. The US National Climate Assessment in 2014 reported that precipitation has increased by 71 percent in the heaviest rainfall events from 1958 to 2012 in the Northeastern states, which include Maryland. This trend is predicted to continue. These data are sufficient cause for concern in how we plan recovery and think about our future. Extreme precipitation is the driver of this disaster, but its effects are exacerbated by two related factors: urbanization and the loss of ecosystems and the flood-protection services they provide. Ellicott City is part of the urban-suburban zone that stretches from Baltimore to the District. The population of the historic town alone tripled in 40 years, going from 21,784 in 1970 to 65,834 in 2010. Supporting the growing suburban population has required major investment in roads and infrastructure. Roads are not designed to simulate flood plains. They neither absorb water nor impede its rapid flow. Paved streets and infrastructure funnel floodwaters into raging torrents, as we saw in shocking videos from Ellicott City. Natural, green infrastructure or ecosystems have traditionally been humans’ first line of defense against natural disasters, including floods, landslides and coastal storms. These services that nature provides were ignored for decades in urban planning. That has cost us dearly economically and in human suffering. It makes sense to turn to nature for help in protecting our communities and reducing costs. Just last month, I spent time at the United Nations University working on ways to create standards and guidelines for incorporating ecosystems into engineering approaches to leverage nature for human protection. We are beginning to see these efforts emerge. For instance, in Wisconsin, the Milwaukee area’sGreenseams project is restoring natural flood plains with wetland areas designed to hold 1.3 billion gallons of water, about 1,970 Olympic-size swimming pools. In Minnesota, Ramsey County developed green infrastructures to reduce localized flooding, decreasing runoff volumes by 99 percent and saving half a million dollars over the cost of gray infrastructure. The Netherlands, a low-lying country that faces extreme flooding, recently created a partnership between the government and the private sector to identify and pursue nature-based solutions that work with engineering approaches to reduce the risks to residents. Ellicott City is indicative of many urban-suburban regions on which this nation depends. There are four action items that Ellicott City, Maryland and all vulnerable communities can complete to leverage nature to recover, plan and protect themselves: ● Estimate the flood damage benefits that green infrastructure can provide; ● Compare the benefits and the costs of using green or gray infrastructure or a mixed (green-gray) option; ● Identify the most effective options among them; and ● Target investments in conservation or restoration to the most cost-effective areas. It is critical that we learn to design infrastructure that can serve more than one purpose. Our solutions to such disasters must align with natural processes, rather than work against them, and be adaptable to cope with changing conditions and extreme events brought on by climate change and sea-level rise. Raising the Stakes on Climate-Change Environmental Policy: White House Issues Guidance on Climate Change in NEPA (EA/EIS). Why it Matters.

Environmental Impact Assessments and Statements that fall under NEPA have been the focus of conflicts and legal disputes over a broad swath of environmental issues. These range from land use including development and restoration e.g. South Florida Everglades Restoration, to transportation and more recently Carbon Emissions and fuel standards. NEPA is a powerful process and its potential use by federal agencies e.g. EPA in addressing climate change has been hotly debated by all sides. Today the White House will issue its final guidance on consideration of greenhouse gas emissions and the effects of climate changeBecause NEPA Process is so pervasive in environmental policy these guidelines have potentially far reaching influence. They are likely to affect all of us either directly in our own lives, and through our work iin the environment and/or for clients. In the weeks ahead there will be new analysis, and we will add to the discussion. The Final Guidance on Consideration of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and the Effects of Climate Change. Federal agencies are required to consider and disclose the potential effects of their actions and decisions on the environment under NEPA. Agency actions can potentially affect climate change by e.g., contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. Alternatively, federal agency actions can be affected by climate change for instance, land use activities including development, restoration, management for endangered species etc. may be affected by changes in the frequency of extreme weather, droughts, wildfires, coastal storms, salt water intrusions etc. The final guidance released today was designed to provide “a level of predictability and certainty by outlining how Federal agencies can describe these impacts by quantifying greenhouse gas emissions when conducting NEPA reviews.” The underlying goal is to give decision makers and the public a greater understanding the potential climate impacts of all proposed Federal actions, and in comparing alternatives and measures that can mitigate them. According to the White House, the new set of guidance also:

NEPA and the EA/EIS: A Snapshot: NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) was enacted in 1969 in response to the Santa Barbara Oil Spill and other environmental activities around that time. Often referred to as the “environmental Magna Carta” it is best known among the public because it governs guidelines and procedures for Environmental Assessments (EA) and Environmental Environmental Impact Statements (EIS). NEPA requires executive federal agencies to disclose the potential environmental effects of their proposed actions and to prepare an EA or full EIS when they significantly affect the environment. Agency activities that trigger NEPA are broad and include any major project at federal, state or local level involving federal funding, or work performed by federal agencies, or that require federal permits. An EIS must identify the potential environmental impacts of a project and evaluate reasonable and prudent alternatives. Public, external party and other federal agency input and comment is part of the EIS or NEPA process. Because all enforcement of NEPA must occur through the court system, it has been front and center in many environmental disputes. The US Supreme Court has decided seventeen NEPA cases. In the last few years NEPA has been invoked in public discourse and in the courts to address climate change and carbon emissions. * Final Guidance will be published on Aug 2, 2016 in the Federal Register Several media recently reported on a scientific study showing the threat to California of a major tsunami generated by an earthquake off Alaska. Nature reinforced the warning soon after with a strong M7.1 earthquake in Alaska. The tsunami threat to California is real. We are not prepared. The immediate economic price tag in infrastructure loss and business interruption is at least $9.5billion. The true costs are much greater. California is not alone. Most ports and coastal communities are ill-equipped to deal with the threats of extreme events from hazards and climate change. I participated in a scientific scenario exercise to assess the potential effects on California of a hypothetical but plausible 9.1 earthquake, originating in Semidi off Alaska. The tsunami generated by the quake would reach N. California in three hours and S. California in six. Long Beach, San Diego, Southern Los Angeles and northern Orange Counties, as well as coastal communities in N. California are most affected. Nearly 92,000 people live inside the expected inundation zone, and 81,000 employees would be there if it struck on a business day; 260,000 visitors would be on coastal beaches and parks. Based on the scenario, fierce currents would roil around the Ports of Los Angeles/Long Beach for two days, The exposure of port trade to damage and that downtime exceeds $1.2billion; business interruption would triple the figure. Along the coast, one-third of all vessels would be damaged or destroyed and over half the docks damaged or lost. The total repair costs for ports, vessels, property and critical infrastructure is estimated at $3.5 billion. Business interruption adds another $6 billion. California’s a leader in protecting and restoring coastal habitats and endangered species, having invested millions of dollars in nature and weathered lengthy and hard-fought environmental battles. Ironically, many of the gains would be swept away in an instant, and species pushed closer to extinction. Ecosystems are not as resilient as they once were and their recovery is uncertain. Coastal areas like Malibu and Laguna are already suffering extreme beach erosion. It is not certain that sand swept away by a tsunami would return. Could these coastal areas continue to pay for re-nourishment and would it be permitted? Marshes can help to buffer the force of the waves. But in marsh areas adjacent to urban zones, e.g., Goleta or Bolinas, many will be filled with debris some of which will be hazardous. Tsunamis trigger cascading disasters that can be more severe and long-lasting than the main event. Fires from gas or petroleum plants are common in a tsunami. Under our scenario, fires would start at many ports and marinas where petrochemicals are stored. In the Port of Los Angeles, there are 117 acres containing 182 storage tanks, with capacity for 6.4million barrels of petroleum products. We found that while fisheries would suffer few direct losses, fishermen would be unable to land or transport their catch to market and could be out of action of months. Fishermen cannot sustain those kinds of downtimes. California’s experienced smaller tsunamis and they serve as a warning. After Tohoku Cresent City had year long delays in recovery; regulators wrangled over environmental concerns before being able to remove tsunami sediments from the port seabed. Santa Cruz also suffered delays. Local, state and federal regulations which work well in normal times become jurisdictional nightmares in a disaster. One reason we are not prepared is that we lack the experience with mega-disasters. Another is because we can’t imagine their effects; they are always different and more far-reaching that we expect. I have experienced this personally, having survived major disasters and worked in their aftermath, For instance, in preparing for tsunamis vessel owners often equate a tsunami in a port as being similar to a big storm believing that the same safeguards will work, they don’t. Working in SE Asia after the tsunami, I encountered many surprised to find no ATM machines or ways to use their credit cards. While aware that buildings and towns had been swept away, the consequences did not sink in until they got there. We all have a naiveté about disasters, until we experience one. But we do not have to manage disaster risks based on personal experiences or perceptions. Many dedicated professionals work hard to prepare and respond to disasters. But we face a challenge to reach the general public and special interest groups. Disaster preparedness is not emergency response, but too often we rely on it as our main tool. Disaster planning means understanding the full range of impacts, managing and reducing the recovery time which often extends into decades. Preparedness reduces the stress on emergency responders. Here are 5 steps that we can take now to better prepare: 1. Scientists civic and business sectors cooperate on science-based scenarios to understand the direct and cascading risks. These collaboration are the only way to fully appreciate the consequences of a hazard and the needs of all sectors. Scientists working alone won’t know what is critical information to businesses or communities. 2. Communities, businesses and trade organizations self-assess to better prepare. 3. Elected officials, scientists, and managers, identify and reach out now to those whom you will need to work with during a disaster. Seeking the environmental regulator in the stress and chaos of a disasters is too late. 4. Governments, special interest groups, civic societies and communities, learn from experiences of others, educate your members and communities. 5. Elected officials and communities, identify cascading disasters, and multiple-hazards, these will play a critical role in the severity of a disaster and the potential to recover, develop resilient strategies. If businesses adopted resilience strategies the interruption costs in our scenario would go down from $6billion to between $500-1200million. Every community and business has the power to assess its risks and to start taking action. Our job as citizens, corporations and civic societies is to take responsibility for knowing our risks and advocate for actions that help keep us and our children safe. Five Critical Steps that Cities, Ports, and Communities can take to prepare for extreme storm, climate change, and tsunami events. Deborah Brosnan Ph.D. |

AuthorDeborah Brosnan Archives

December 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed