|

I recently cruised through French Polynesia and the Cook Islands as an invited speaker on ocean science. Sailing into turquoise lagoons, diving on vibrant reefs, and watching whales and dolphins play—here was Paradise Found. These islands are not immune to climate change effects but I found many fewer vulnerabilities.

Like most ecological scientists, I work in distressed habitats and with communities facing tough choices about their natural and economic resources. I am used to loss being the messenger for action. But here in French Polynesia, the messenger took a new and unfamiliar form—an absence of flagrant problems. Beauty and bounty in Paradise are teaching us three lessons that we must heed today. 1. Natural luck matters. On Bora Bora, I spent time with a guide who was leading a drift snorkel through the reef channel. As we hiked across the landscape to our entry point he described his reasons for living in the islands. Economically, including by developed-world standards, he made a good income from coral reef and nature-based tourism. His personal downtime to rejuvenate was spent surfing or offshore fishing with friends. Family time involved teaching his son to line-fish in the lagoon. This trinity of values—economics, personal well-being, and family—the very attributes that we promote as the basis of healthy individuals, communities and nations, are amply supplied here by ecosystems. There are of course other sources of social or economic benefits in the region but for many, nature is the underlying provider. These islands are volcanic mountains surrounded by wide lagoons and fringing coral reefs. The reef-lagoon system is similar to a castle’s moat and wall, and plays a similar role defending the land from the full onslaught of the Southern Ocean. Large swells sweeping up from Antarctica continuously crash in mountains of white water on the outer fringing reefs. . Without these fringing reefs, lagoons would vanish and shorelines erode rapidly. Corals provide a stability that has allowed communities to build houses, schools and businesses at the waters edge, and has given them easy access to the rich waters. Fertile volcanic soils, a source of high productivity, are stabilized by lush forests. The sense of abundance that permeates the islands springs from their natural legacy. 2. Don’t squander your ecological inheritance Some places are lucky. They have the kinds of natural systems that make them less vulnerable to climate change and hazards. Others are not. The twenty-nine atolls of the Marshall Islands are tragically disappearing. Barely six-feet above sea level and most less than a mile wide, they are already feeling the sharp bite of climate change. Sea level has risen by a foot over the past 30 years, driven partly by changing trade wind patterns. The islands’ pleas for help at Paris CoP21 and since still ring in our ears. The eastern seaboard of the USA is already experiencing coastal inundations and flooding from the dual challenges of land subsidence and rising sea level. The natural luck of places like French Polynesia can be destroyed in an instant. Around the world, poor environmental planning is rampant. There are too many ill-conceived projects, such as the ones that destroy reefs and fail to account for their roles in beach and shoreline protection. Infrastructure that lacks absorption capacity but is built on flood plains can vastly worsen the effects of rain, even causing devastating floods. 3. Understand your own environmental reality, then take action. For three weeks, I shared the ocean’s beauty and magic with travelers who often expressed concerns for the future of our seas. At the end of the voyage, guests returned to the realities of home where they faced challenges of urbanization, environmental destruction, economic worries, socio-political upheaval; all sorts of stresses and fears, of which climate change is one more. And as stresses go, climate change is big and global, so overwhelming that people can feel compelled to ignore it, even if they’d rather not. But along with the souvenirs, selfies, and memories, the islands gave us a vital message to carry with us. By knowing our own environment we have the power to make changes that will matter. How?

Global challenges like climate change are overwhelming. We can’t solve the world’s problems alone, but we can make an important difference where we live. A trip to paradise teaches us why we should. *I was fortunate to explore the Islands as invited expert on board MS Paul Gauguin. Views expressed are my own. Reproduced kindly from Huffington Post http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/585cb489e4b068764965bbc3?timestamp=1482506579978

1 Comment

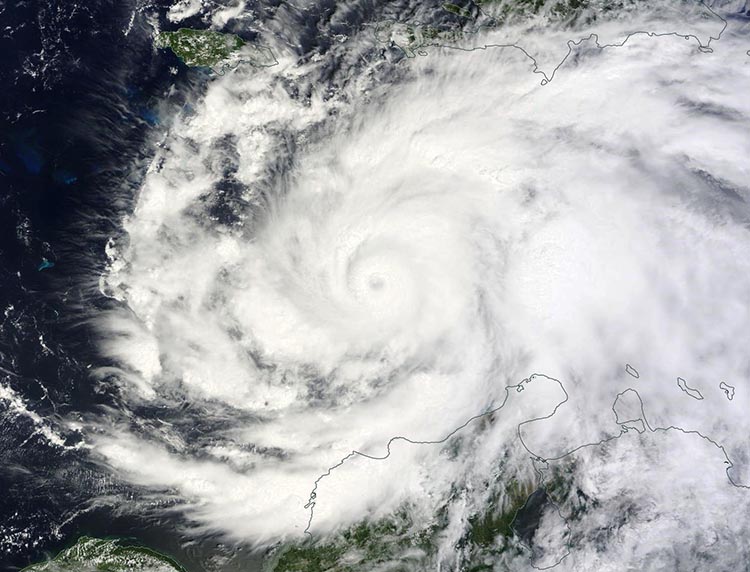

This week the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals issued a game-changing ruling strengthening the link between climate change projections and the listing of endangered species. The decision will affect management of public and private lands. It will also transform future species’ listings, what constitutes best available science, and levels of scientific uncertainty acceptable in courtrooms. On Monday, the justices upheld the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) to list the Beringia Bearded Seal (Erignathus barbatus nauticus) as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The underlying basis was not an immediate threat to the seal or even declining numbers. It rested on changes to sea ice (their habitat) that are projected to occur off Alaska as far out as 2095, and based on the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) models. The Beringia Bearded Seal lives on patches of ice floes over shallow waters in the Bering and Chuckchi Sea. They use these habitats for feeding, breeding, nursing, molting and protection against predators. In 2008 the Center for Biological Diversity petitioned NMFS to list the seals under ESA citing global warming as the primary threat. NMFS first set out to establish the importance of ice floes as essential to the survival of the seal, and which it did using observational studies and peer review. NMFS then turned to IPCC climate change models. These project that by 2050 between 80% and 100% of summer ice floes will have disappeared during the seals’ critical life phases. NMFS examined the projections from 2050 to 2095 which show all summer ice will be gone over most of the seals’ range. Models from 2050 forward are more volatile because they can’t account for unforeseen factors (e.g. technology or policy breakthroughs). Taking all these data into account and involving two round of peer-review, NMFS determined to list the seal as a threatened Distinct Population Segment under ESA. The State of Alaska, Oil and Gas Interests, and Native Tribes challenged NMFS decision. The 9th circuit court in San Francisco affirmed NMFS listing on the basis that the Service had used the best science available and reasonably. ESA, the justices noted, only requires best available science, not iron clad science nor at a too high a standard. Despite the volatility of climate projections from 2050-2095 the court concluded that this doesn’t deprive them of use in rule making. The justices made a comment that may freeze many in their tracks. “Although Plaintiffs framed their arguments as challenging the long-term climate projections they seek to undermine NMFS use of climate change projections as the basis for ESA listings.” The court was having none of this. Climate-change models and projections even with uncertainties, they find, constitute the best available science. At the end of the day this case turned on one critical question- “When NMFS determines that a species that is not presently endangered will lose its habitat due to climate change by the end of the century, may NMFS list that species as threatened under the Endangered Species Act?” The 9th circuit court has answered with a definitive “yes”. Reproduced with kind permission from Huffington Post. For a more indepth analysis of the science and ruling download this analysis or read it here in linkedin Bearded Seal Image courtesy of NOAA wiAs Category 4 Hurricane Matthew strikes Jamaica and takes direct aim at Cuba and Haiti, extensive efforts are being made to safeguard lives and property. With winds over 130 mph (209km/hr.) the storm is expected to bring 40 inches (1,016 mm) of rain and severe coastal surge. As vital as these actions are, it is also important to understand that the state of a region’s environment can render it safer or at greater risk of harm when disaster strikes. Action taken now and in the aftermath can save lives, protect property, and keep the economy afloat.

Ecosystem health can ameliorate or exacerbate the effects of hurricanes, during the event itself and several days or weeks after the event has passed. Through ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction we’ve learned a great deal about when and how ecosystems affect risks. Here are some lessons learned for communities and responders to keep in mind to help safeguard communities and identify places that may have different or additional risks. Ecosystem health can ameliorate or exacerbate the effects of hurricanes during the event itself, and for several days or weeks after the storm has passed. The consequences for life and property have often been devastating. Through ecosystem based disaster risk reduction we’ve learned a great deal about when and how ecosystems affect risks, but these factors are not yet mainstreamed into disaster management. Here are some lessons learned for entities and responders to use now in order to help safeguard communities and identify places that may have additional risks. Deforestation increases the risk of flash floods and mudslides. Mudslides can occur days or even weeks after a hurricane. In Haiti severe deforestation has left large areas vulnerable. Downstream communities, even those less affected by wind and storm surge, may be exposed. Be aware of these risks and know that they can continue for some time after the immediate danger has passed. In some communities stabilizing the soil and safeguarding villages or settlements from mudslides will be a higher post-storm priority. The confluence of rivers and sea is a dangerous zone in a hurricane. This is where storm surge meets raging river floodwaters. Risks are exacerbated if there has been upstream slope deforestation or developments that reduce absorption capacity. The tragic loss of Petite Savanne in Dominica during tropical storm Erika in 2015 reminds us to pay close attention to these areas and to those who live there. Located on the coast at the mouth of the river, a combination of flooding and surge destroyed the historic town with loss of live. The remaining residents were permanently relocated to other places. Towns villages and critical infrastructures located on low-lying coastal zones or on flood plains are exposed to surge and flooding. Risks and impacts can be higher than expected if the ecosystems around them have been degraded and they cannot function as they once did. For communities, businesses, and emergency responders an awareness of the ecological role in hazards and disasters is a valuable tool in their emergency response toolbox. It can reduce immediate and short-term damage and help to prioritize recovery actions to benefit those affected. Incorporating ecosystems into disaster management will be even more critical as sea levels rise and climate change become more pronounced. Lives, businesses, and communities are at stake. During this hurricane and throughout the season we hope that all will stay safe and secure. PUBLISHED WITH PERMISSION FROM MY HUFFINGTON POST ARTICLE Published on New York Times Opinion Dotearth with acknowledgement to Andrew Revkin Andrew Revkin at New York Times Doearth and through the tragedy of the recent Italian earthquake, sparked an important question on why people live in disaster zones and the challenges of engineering for hazard zones. He invited me to submit a comment. His original and thoughtful piece along with my comment is posted here and my comment is in the blog below.

New York Times: 6:3o p.m. | Deborah Brosnan, a scientist focused on disaster risk reduction (and an author of an important report on planning for extreme geohazards), sent this relevant reflection: A sense of place is core to all cultures. The older the culture the deeper the sense of place. The U.S. is a new country. It has a stronger sense of political identity than it does of physical structures and places. Our treatment of this complex issue is not as sophisticated as it needs to be. We send mixed messages. Humans have traditionally settled in harm’s way because natural hazards are associated with resources that we need, like water and food. Cultures persist when the losses do not destroy them completely. In conservation, we acknowledge and vigorously foster the sense of place as the critical bond between humans and their environment. We argue that it’s key to sustaining our planet. Yet when hazards become disasters we focus on the dangerous “place.” I grew up in the west of Ireland where the sense of place was enshrined and all-defining. Many of my ancestors had left during a disaster known as “the famine” and the ruins of their homes still dotted the landscape. For those who didn’t leave the bond between land and people grew stronger, and having land was a mark of a person’s worth. When I worked in Sri Lanka after the Southeast Asia tsunami, many of the displaced survivors were housed in U.N. tent communities. But during the day or even at night, they’d go home. I saw them sitting on makeshift chairs in places where there was barely a foundation left or nothing at all. Their “home” was their only anchor in a world that had been turned upside down, and where other anchors like family and friends were gone. But they were also afraid, fearful that if they didn’t protect their property then someone else would move in and squatters would take possession. I witnessed similar feelings and behaviors when working through the volcanic eruption in Montserrat. A nation’s cultural history, relationship to natural resources, and frequency of hazards all determine the sense of place and the meaning of leaving or changing. Rural Italy, like the west of Ireland, has a deep sense of home; however risky, it’s an established known. This is a complex subject that runs deep in our D.N.A. and evolutionary history. The way we handle it will determine how well we navigate climate change. Thanks for starting the conversation that we need to be having. Deborah Brosnan If you are involved in producing, reducing, or managing carbon emissions, then listen-up because this will affect you.

Last week the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals might just have made one of the most critical climate change rulings to date. By affirming the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC), it will encourage other regulators to use carbon costs in setting policies, and may pave a way for a Carbon Tax – an idea much feared by some. But it also offers an opportunity for companies to quantify and communicate the energy value of their technologies, and the dollar value of their environmental and social practices. In a Chicago courtroom, the justices (all, incidentally, appointed by Republican Administrations) upheld the Department of Energy’s (DoE) metric on the Social Cost of Carbon, under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA) of 1975. EPCA was enacted in the wake of the Oil Embargo on petroleum exports to the US by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries in 1973-74. EPCA was enacted to help and protect the US through the use of energy conservation measures. In 2014, the DoE issued two rules, one set the energy efficiency standards for 49 classes of commercial refrigeration equipment and the second stipulated the test procedures to be used. Several industry groups filed suit challenging the substance of the rules and the decision-making processes used by DoE to make them. One of the challenges concerned the Social Cost of Carbon (SSC) metric which DoE used in its cost-benefit analysis for setting new standards, an analysis required since 1981 whenever the agency considers new regulation. The SCC represents the economic cost of damages associated with a one metric ton of Carbon in a given year. (The same figure represents the value of damages avoided for a reduction in Carbon). The metrics were generated by an interagency panel comprising experts in science and economics from 15 agencies and first formed in 2009. The current dollar value is US$37* per ton. What does this mean? If for example tightening certain emissions standards lowers carbon output by say 3 million tons per year, then multiply the number by $37 and you have the total damages avoided ($110million). SCC is designed as a comprehensive estimate of climate change damages and includes among other factors, changes in net agricultural productivity, human health, property damages from increased flood risk, and changes in energy costs (heating and air conditioning). It does not however include all kinds of important damages e.g. extreme disasters are excluded. For the proposed rules on commercial refrigerators, DoE calculated that the new conservation standards would cost manufacturers between $93.6 and $165 million per year. At the same time the projected total benefits to consumers was estimated at between $4.9 and $11.3 billion, including in green house gas reductions and consumer savings. DoE used the analysis as one criterion to justify the standards. The petitions challenged the figures and the methods but the court repeatedly sided with DoE. The petitioners argued that in its calculations the DoE arbitrarily considers the benefits accruing to the global environment and to all people around the world, but only considers the costs on a national level. DoE argued that climate change involves a global externality, meaning that carbon released in the US affects the entire world. National energy conservation, the agency argued, has global effects and these are an appropriate consideration for national policy. The court agreed with DoE. In its 68 page ruling, the court denied the petitions for review in their entirety. The implications of the ruling are enormous. First the court definitely ruled on the legality of carbon accounting, and the use of quantitative measures of carbon cost-benefits. We can anticipate more regulators to incorporate SCC when considering and justifying the need for new or revised environmental regulations The acceptance of a quantitative carbon accounting provides a dollar value that has potential implications for a Carbon Tax. This is a highly controversial topic. Several entities feel that there must be and will be a carbon tax while others are vehemently opposed. The ruling may be good news for certain businesses. Deriving a dollar figure for carbon will help businesses plan for the long term. Being able to credibly quantify costs and benefits of new technologies and corporate actions has long been an impediment to companies. Consumers and shareholders relate to numbers. Companies will now be able to disclose their environmental and social performance to shareholders and stakeholders and in better and standardized way. The case was a complex one involving science, economics and policy. There are many lessons in the ruling including for scientists as well as environmental attorneys who use science in their practice. Critical to the case was the conclusion that the agencies had relied on science that met the current professional or industry standard, was peer reviewed and evaluated in an open and transparent manner. The court also considered and accepted the use scientific uncertainty standards, something that can be challenging in courts and a rarity in complex situations especially regarding climate change. The social cost of carbon once an emerging instrument in putting a price on carbon has just become the center-piece. *(Several entities argue the figure is too low e.g. a recent Stanford Study calculate SCC at $220 per ton) This appeared as an Opinion Piece in the Sunday Washington Post here Thanks to the Post for publishing this opinion.

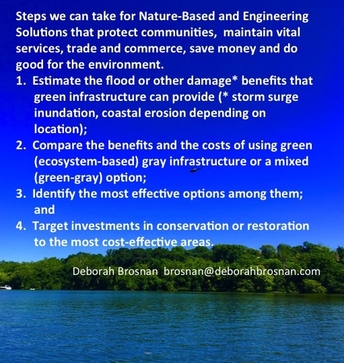

Last weekend we witnessed incredible devastation and tragic loss of human life in Ellicott City. The full scope of the disaster won’t be assessed for some time. For many residents, just feeling safe again will be challenging. Ellicott City sprung up in a bucolic countryside surrounded by rivers and streams and is naturally prone to flooding from the Patapsco River and Tiber Creek. Flash flooding from this storm, which dropped about six inches of rain in two hours, was an extreme event but one that may become more common. The US National Climate Assessment in 2014 reported that precipitation has increased by 71 percent in the heaviest rainfall events from 1958 to 2012 in the Northeastern states, which include Maryland. This trend is predicted to continue. These data are sufficient cause for concern in how we plan recovery and think about our future. Extreme precipitation is the driver of this disaster, but its effects are exacerbated by two related factors: urbanization and the loss of ecosystems and the flood-protection services they provide. Ellicott City is part of the urban-suburban zone that stretches from Baltimore to the District. The population of the historic town alone tripled in 40 years, going from 21,784 in 1970 to 65,834 in 2010. Supporting the growing suburban population has required major investment in roads and infrastructure. Roads are not designed to simulate flood plains. They neither absorb water nor impede its rapid flow. Paved streets and infrastructure funnel floodwaters into raging torrents, as we saw in shocking videos from Ellicott City. Natural, green infrastructure or ecosystems have traditionally been humans’ first line of defense against natural disasters, including floods, landslides and coastal storms. These services that nature provides were ignored for decades in urban planning. That has cost us dearly economically and in human suffering. It makes sense to turn to nature for help in protecting our communities and reducing costs. Just last month, I spent time at the United Nations University working on ways to create standards and guidelines for incorporating ecosystems into engineering approaches to leverage nature for human protection. We are beginning to see these efforts emerge. For instance, in Wisconsin, the Milwaukee area’sGreenseams project is restoring natural flood plains with wetland areas designed to hold 1.3 billion gallons of water, about 1,970 Olympic-size swimming pools. In Minnesota, Ramsey County developed green infrastructures to reduce localized flooding, decreasing runoff volumes by 99 percent and saving half a million dollars over the cost of gray infrastructure. The Netherlands, a low-lying country that faces extreme flooding, recently created a partnership between the government and the private sector to identify and pursue nature-based solutions that work with engineering approaches to reduce the risks to residents. Ellicott City is indicative of many urban-suburban regions on which this nation depends. There are four action items that Ellicott City, Maryland and all vulnerable communities can complete to leverage nature to recover, plan and protect themselves: ● Estimate the flood damage benefits that green infrastructure can provide; ● Compare the benefits and the costs of using green or gray infrastructure or a mixed (green-gray) option; ● Identify the most effective options among them; and ● Target investments in conservation or restoration to the most cost-effective areas. It is critical that we learn to design infrastructure that can serve more than one purpose. Our solutions to such disasters must align with natural processes, rather than work against them, and be adaptable to cope with changing conditions and extreme events brought on by climate change and sea-level rise. Raising the Stakes on Climate-Change Environmental Policy: White House Issues Guidance on Climate Change in NEPA (EA/EIS). Why it Matters.

Environmental Impact Assessments and Statements that fall under NEPA have been the focus of conflicts and legal disputes over a broad swath of environmental issues. These range from land use including development and restoration e.g. South Florida Everglades Restoration, to transportation and more recently Carbon Emissions and fuel standards. NEPA is a powerful process and its potential use by federal agencies e.g. EPA in addressing climate change has been hotly debated by all sides. Today the White House will issue its final guidance on consideration of greenhouse gas emissions and the effects of climate changeBecause NEPA Process is so pervasive in environmental policy these guidelines have potentially far reaching influence. They are likely to affect all of us either directly in our own lives, and through our work iin the environment and/or for clients. In the weeks ahead there will be new analysis, and we will add to the discussion. The Final Guidance on Consideration of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and the Effects of Climate Change. Federal agencies are required to consider and disclose the potential effects of their actions and decisions on the environment under NEPA. Agency actions can potentially affect climate change by e.g., contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. Alternatively, federal agency actions can be affected by climate change for instance, land use activities including development, restoration, management for endangered species etc. may be affected by changes in the frequency of extreme weather, droughts, wildfires, coastal storms, salt water intrusions etc. The final guidance released today was designed to provide “a level of predictability and certainty by outlining how Federal agencies can describe these impacts by quantifying greenhouse gas emissions when conducting NEPA reviews.” The underlying goal is to give decision makers and the public a greater understanding the potential climate impacts of all proposed Federal actions, and in comparing alternatives and measures that can mitigate them. According to the White House, the new set of guidance also:

NEPA and the EA/EIS: A Snapshot: NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) was enacted in 1969 in response to the Santa Barbara Oil Spill and other environmental activities around that time. Often referred to as the “environmental Magna Carta” it is best known among the public because it governs guidelines and procedures for Environmental Assessments (EA) and Environmental Environmental Impact Statements (EIS). NEPA requires executive federal agencies to disclose the potential environmental effects of their proposed actions and to prepare an EA or full EIS when they significantly affect the environment. Agency activities that trigger NEPA are broad and include any major project at federal, state or local level involving federal funding, or work performed by federal agencies, or that require federal permits. An EIS must identify the potential environmental impacts of a project and evaluate reasonable and prudent alternatives. Public, external party and other federal agency input and comment is part of the EIS or NEPA process. Because all enforcement of NEPA must occur through the court system, it has been front and center in many environmental disputes. The US Supreme Court has decided seventeen NEPA cases. In the last few years NEPA has been invoked in public discourse and in the courts to address climate change and carbon emissions. * Final Guidance will be published on Aug 2, 2016 in the Federal Register Several media recently reported on a scientific study showing the threat to California of a major tsunami generated by an earthquake off Alaska. Nature reinforced the warning soon after with a strong M7.1 earthquake in Alaska. The tsunami threat to California is real. We are not prepared. The immediate economic price tag in infrastructure loss and business interruption is at least $9.5billion. The true costs are much greater. California is not alone. Most ports and coastal communities are ill-equipped to deal with the threats of extreme events from hazards and climate change. I participated in a scientific scenario exercise to assess the potential effects on California of a hypothetical but plausible 9.1 earthquake, originating in Semidi off Alaska. The tsunami generated by the quake would reach N. California in three hours and S. California in six. Long Beach, San Diego, Southern Los Angeles and northern Orange Counties, as well as coastal communities in N. California are most affected. Nearly 92,000 people live inside the expected inundation zone, and 81,000 employees would be there if it struck on a business day; 260,000 visitors would be on coastal beaches and parks. Based on the scenario, fierce currents would roil around the Ports of Los Angeles/Long Beach for two days, The exposure of port trade to damage and that downtime exceeds $1.2billion; business interruption would triple the figure. Along the coast, one-third of all vessels would be damaged or destroyed and over half the docks damaged or lost. The total repair costs for ports, vessels, property and critical infrastructure is estimated at $3.5 billion. Business interruption adds another $6 billion. California’s a leader in protecting and restoring coastal habitats and endangered species, having invested millions of dollars in nature and weathered lengthy and hard-fought environmental battles. Ironically, many of the gains would be swept away in an instant, and species pushed closer to extinction. Ecosystems are not as resilient as they once were and their recovery is uncertain. Coastal areas like Malibu and Laguna are already suffering extreme beach erosion. It is not certain that sand swept away by a tsunami would return. Could these coastal areas continue to pay for re-nourishment and would it be permitted? Marshes can help to buffer the force of the waves. But in marsh areas adjacent to urban zones, e.g., Goleta or Bolinas, many will be filled with debris some of which will be hazardous. Tsunamis trigger cascading disasters that can be more severe and long-lasting than the main event. Fires from gas or petroleum plants are common in a tsunami. Under our scenario, fires would start at many ports and marinas where petrochemicals are stored. In the Port of Los Angeles, there are 117 acres containing 182 storage tanks, with capacity for 6.4million barrels of petroleum products. We found that while fisheries would suffer few direct losses, fishermen would be unable to land or transport their catch to market and could be out of action of months. Fishermen cannot sustain those kinds of downtimes. California’s experienced smaller tsunamis and they serve as a warning. After Tohoku Cresent City had year long delays in recovery; regulators wrangled over environmental concerns before being able to remove tsunami sediments from the port seabed. Santa Cruz also suffered delays. Local, state and federal regulations which work well in normal times become jurisdictional nightmares in a disaster. One reason we are not prepared is that we lack the experience with mega-disasters. Another is because we can’t imagine their effects; they are always different and more far-reaching that we expect. I have experienced this personally, having survived major disasters and worked in their aftermath, For instance, in preparing for tsunamis vessel owners often equate a tsunami in a port as being similar to a big storm believing that the same safeguards will work, they don’t. Working in SE Asia after the tsunami, I encountered many surprised to find no ATM machines or ways to use their credit cards. While aware that buildings and towns had been swept away, the consequences did not sink in until they got there. We all have a naiveté about disasters, until we experience one. But we do not have to manage disaster risks based on personal experiences or perceptions. Many dedicated professionals work hard to prepare and respond to disasters. But we face a challenge to reach the general public and special interest groups. Disaster preparedness is not emergency response, but too often we rely on it as our main tool. Disaster planning means understanding the full range of impacts, managing and reducing the recovery time which often extends into decades. Preparedness reduces the stress on emergency responders. Here are 5 steps that we can take now to better prepare: 1. Scientists civic and business sectors cooperate on science-based scenarios to understand the direct and cascading risks. These collaboration are the only way to fully appreciate the consequences of a hazard and the needs of all sectors. Scientists working alone won’t know what is critical information to businesses or communities. 2. Communities, businesses and trade organizations self-assess to better prepare. 3. Elected officials, scientists, and managers, identify and reach out now to those whom you will need to work with during a disaster. Seeking the environmental regulator in the stress and chaos of a disasters is too late. 4. Governments, special interest groups, civic societies and communities, learn from experiences of others, educate your members and communities. 5. Elected officials and communities, identify cascading disasters, and multiple-hazards, these will play a critical role in the severity of a disaster and the potential to recover, develop resilient strategies. If businesses adopted resilience strategies the interruption costs in our scenario would go down from $6billion to between $500-1200million. Every community and business has the power to assess its risks and to start taking action. Our job as citizens, corporations and civic societies is to take responsibility for knowing our risks and advocate for actions that help keep us and our children safe. Five Critical Steps that Cities, Ports, and Communities can take to prepare for extreme storm, climate change, and tsunami events. Deborah Brosnan Ph.D.  INSIGHTS Practical Information for environmental risks and solutions. Guiding Principles for integrating ecosystems into infrastructure and broadscale solutions for mitigating hazards and climate change Increasingly, we are asked for guidance on how to integrate engineering and ecosystem solutions to hazard, climate change and development decisions. Requests come from across the board at all scales, and noticeably from island nations where decision-makers are responsible for multiple sectors. Mistakes are costly and may not be fixable. Ecosystems provide essential services to humans in mitigating hazards and climate change. Coral reefs, mangroves, wetlands, forested hillsides, and sand dunes can protect humans from hazards like hurricanes, storm surges and landslides. There is growing interest in leveraging these services to create cost-effective solutions that protect human enterprise and communities. The value to humanity from robust ecosystem-based solutions can be huge but the cost from poorly designed ones can be vast, and create a crisis of confidence in the idea of building with nature. In the aftermath of the SE Asia tsunami there was high interest and investment in mangrove restoration. At least 75% of the efforts failed. Poor planning and implementation, planting of mangroves in unsuitable habitats, planting of wrong species are among the reasons for the high failure rate. These kinds of mistakes can be avoided by using guidelines and standards. Here are 10 principles based on experience. Guiding Principles. 1. Do no harm. In a time when nature is under threat, there’s often an unstated assumption that attempts to restore biodiversity and ecosystems carry no negative consequences. But building with ecosystems can have harmful effects if projects are not properly evaluated or carried out. Introduction of non-native species, attempting to establish species or ecosystems in unsuitable habitats, restorations that create future health or economic risks are not positive actions and need to be avoided. Assess the positive and potential negative impacts of any nature-based project. 2. Identify the problem/problems to be solved. It is not unusual for clients or entities to define an important part of a problem the face and fail to articulate their deeper expectations or needs. Defining the problem is more challenging than generally perceived. Spend time in assessing the full suite of issues on the table to be solved, and the role that ecosystems can play in solutions. This will take more time than you imagine but it is one of the most critical steps. Otherwise you may solve the wrong problems or priorities, albeit very well. 3. Identify and assemble the best-qualified team. The previous step (2) will enable you to define the expertise and skillset needed for the team. For instance, when working on endangered species issues as part of a major and controversial restoration, our client initially felt that we needed a panel of endangered species experts to resolve problems associated with their potential extinction and recovery. However, as we worked to understand the issues more deeply, it became clear that involving habitat experts, hydrologists and engineers would be critical to finding a solution. By engaging the best and a complete team we were able to provide real and workable solutions. We were also able to get to solutions quicker because the right team was in place. Be comfortable knowing that you will likely have to reach outside your domain for the right expertise - just because you don’t know it doesn’t mean it’s not important. The right team matters. 4. Listen to the community but be professional. Community concerns, knowledge and wishes must be taken into account. Otherwise the risk of failure is high. However, for modern challenges, these projects need the best of human know-how. They are and should be considered professional undertakings that will involve expert knowledge, high-level skills, and professional judgment. 5. Understand the system or systems. Invest in knowing the system. What are key dynamics, drivers, current conditions and likely system performances overtime and under different scenarios? What ecosystem services are expected? What is the likelihood that the project can deliver them and at what levels of performance and confidence? How will the ecosystem interact with all the other activities and developments? Addressing these kinds of questions generate long-term solutions. 6. Risks and Uncertainty. Be honest with clients and communities about the risks and uncertainties. These are the two elements that most frame their decision space. Individuals and entities are more able and comfortable making decisions when these presented to them. Too often risks are identified without uncertainty or vice versa. Situations where risks are high and there is high uncertainty require different decision-criteria to situations of low risk and high uncertainty. 7. Identify the range of options that offer solutions. Consider tradeoffs, costs, and expectations associated with each option. For instance, an ecosystem-based approach may be at best an experimental solution. This can be a viable and ethical option if the community is informed, on-board, and proper precautions and monitoring are included. Where possible evaluate the benefits and losses associated with an ecosystem-based, a hybrid (ecosystem-engineering mix), or engineering solutions. 8. Address practicalities. How workable are the solutions given factors such as governance, regulations, scale, community acceptance, financing or other restrictions? Evaluate each alternative in relation to practicalities, and articulate the range of solutions to communities and clients. 9. Prepare all elements of the project for implementation. Prepare appropriately, especially when projects require many inter-dependent steps. 10. Monitor and report. Monitor the results. Use an adaptive management approach so that current and future projects can learn from the effort and in order to continually improve decisions and implementation. Report transparently, clearly and often to clients/stakeholders. Deborah M Brosnan Ph.D. Innovating engineering and ecosystem-based approaches for disaster risk reduction & climate change *6/22/2016  Thoughts from an International Science-Policy Workshop. Recently at the invitation of the UN and PEDRR (Partnership for Environment and Disaster Risk Reduction**), I was fortunate to participate in and facilitate at a small but powerful international gathering on integrating engineering and ecosystems approaches into Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change. I flew to Bonn Germany, birthplace of Beethoven, for an intensive three-days of work at the UN Campus. Emerging challenges associated with population growth, urbanization (by 2050 over half the world’s population will live in coastal cities), economic development, sea level rise and changing climate patterns will require fresh approaches and answers. New solutions will need to be innovative and align engineering infrastructure with environmental protection and economic growth. Nature is a critical player but not the only one in this kind of thinking. The concept of nature-based solutions or building with nature is becoming more mainstream as society struggles to find answers and while an expanding population puts more demands on scarce and stressed resources. But not everyone is convinced that nature is as secure as concrete. The Bonn gathering brought together thinkers and practitioners from around the world representing most of the planet’s ecosystems and interests. Experiences spanned national, urban, and rural scales. There were experts in economics, finance, engineering, ecology, social sciences, and from academic, government, NGO, institutional and the private sectors. All had an important voice. Integrating ecosystem services with engineering is necessary but complex. Some nations have already embraced the concept and invested heavily to explore solutions. In the Netherlands, government, private and academic sectors joined together with an investment of $30million over five years to collaborate on this challenge. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, known for its huge infrastructure projects, has been exploring guidelines and approaches to include nature in their designs. NGO communities like The Nature Conservancy, Environmental Defense Fund, Wetlands International and others have actively been supporting nature-based solutions. Japan has been learning from post Tohoku efforts. Academics and university programs like UN-University, the Global Forum for Urban and Regional Resilience (Virginia Tech), programs in Singapore, Spain, Germany and beyond have sought to facilitate dialogues and cross-disciplinary interactions as well as engaging in research projects. Professional engineering societies, e.g. American Society of Civil Engineers, are seeking ways to adapt their practices to include green solutions and address climate change. The UN and PEDRR continue to provide a forum for these efforts. For three full days we worked in plenary and small groups, holding spirited debates to explore the challenges and identify action priorities that would help us to get closer to solutions. Participants shared their knowledge and opinions. They described on the ground experiences from large to small-scale projects, lessons learned, and views on how to make progress ranging from integrated design to procurement practices. I facilitated the first day of discussion on engineering and ecological guidelines, and approaches. While engineers work to well-honed specifications seeking a fixed and stable outcome, ecosystem scientists focus on processes, their approach is to facilitate ecosystem dynamics that will result in habitat changes over time. A challenge is to bring these two kinds of systems and thinking together. Codes of practice, issues of client versus beneficiary, liability, reliability, and community engagement were much discussed. Ecological-Engineering is a multi-functional effort and one that will require long-term focus and demonstration pilot projects. It is critical to be clear to communities and clients the benefits and losses associated with ecosystem only, engineering only, and hybrid (ecosystem-engineering) solutions. Cost is always a driver of what is possible. Engineering solutions can mean higher building and maintenance cost compared to nature-based or hybrid ones. The question is whether the costs are justified for the benefits, or whether risks are perceived as too great to leave the solution to nature. Communities vary in their knowledge of nature, their uses of their natural resources, and the level of risks that they are willing to bear. Balancing the input of community knowledge with professional approaches and implementation needs to be considered. Nature-based projects should not be based only on local volunteerism since they require professional expertise and often involve large engineering works. Economic costs, incentives and financing for solutions will play a driving role in whether the best options are implemented or not. Five umbrella priority Items were identified by the group for deeper exploration by the PEDRR partnership and participants themselves. Before the end of the gathering each group had identified specific next steps, with timelines and responsible parties. Everyone felt the urgency to move from ideas to action. The overarching priorities are briefly summarized as:

In the city of Beethoven we did not compose a musical masterpiece, we did however collectively create a dynamic symphony with disparate but harmonic voices working towards a common opus. Deborah Brosnan Ph.D *Thank you to the UN and PEDRR especially to Marisol Estrella, Fabrice Renaud, Karen Sudemeir, Muralee Thummarukudy, Zita Sebesvari and Jakob Rhyner, who were instrumental in conceiving and organizing this effort. My deep appreciation to all who participated and engaged. Personal opinions are my own. This is an inclusive effort that welcomes the participation of professionals and societies who can and wish to contribute. Please make contact if you are interested in knowing more and/or collaborating **Formally established in 2008, the Partnership for Environment and Disaster Risk Reduction (PEDRR) is a global alliance of UN agencies, NGOs and specialist institutes (pedrr.org). Image, top and bottom left courtesy of PEDRR and Karen Sudermeir, others Debraoh Brosnan. |

AuthorDeborah Brosnan Archives

December 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed